The history’s whims are fascinating. The impulse for the reunification of Prussia and the flourishing of Breslau as a European metropolis was… a failure with the French! In 1807 Hieronim Bonaparte conquered the city after a fierce battle. He ordered – the defence walls to be demolished! He wanted to humiliate the enemy, expose him. Meanwhile – he let the air in between the narrow streets and alleys. And unintentionally contributed to the dynamic development of the Silesian capital city. Of the approximately 60,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the 19th century, by 1913 there were already well over 500,000. And these proud citizens of Breslau decided to celebrate the 100th jubilee of Frederick William III’s appeal and triumph at Leipzig. How?

By showing the whole world the history and economic strength of the Silesia. There was planned a large exposition, following the example of the World Exhibitions, which we know today as EXPO. And since the Eiffel Tower was built in Paris in 1889 on a similar occasion, in Breslau the intention was to also organize something spectacular. But where to accommodate thousands of exhibitors and visitors? It was necessary to design a new space, successfully combining trade fair, exhibition and recreational functions, which would serve as an arena for further industrial, cultural and sports events. In the vicinity of one of the older zoological gardens in the world (Zoo Wrocław was established in 1865), a large plot of land was staked out and a call for tenders was launched. The concept of the urban architect, Max Berg, was selected from among 43 submitted projects. Visionary. Innovative. Pioneering. But expensive – 1.9 million of the Deutsche Marks.

Technology of the future

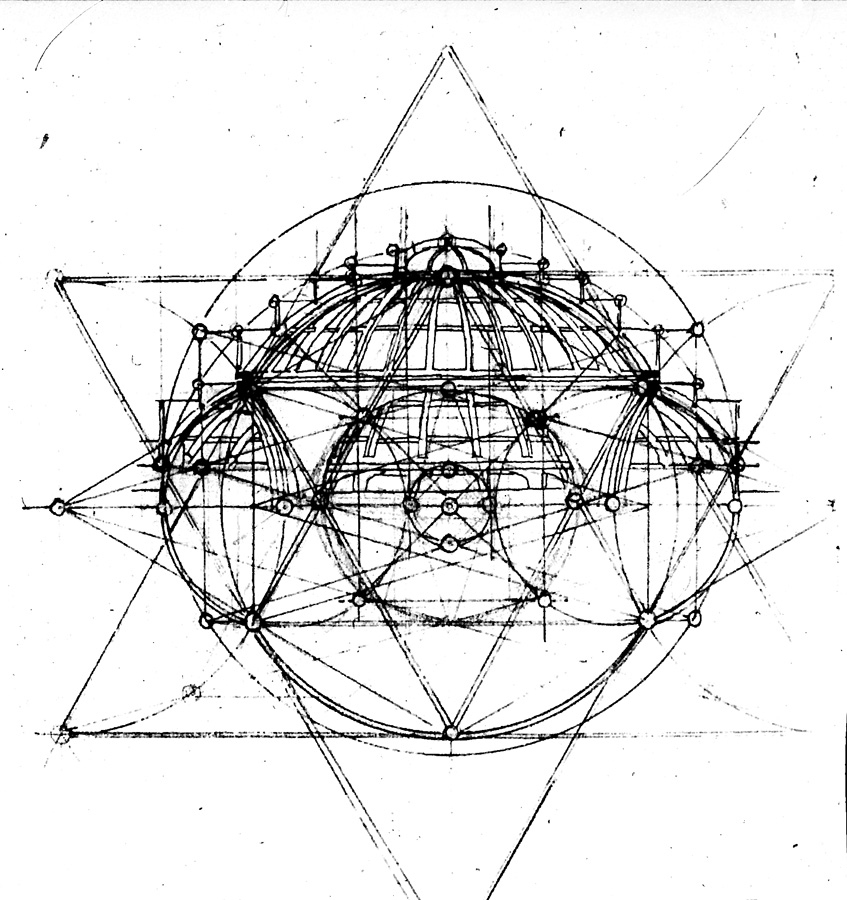

On 28 June 1911, the project received a formal building permit. The function-driven form translated into specific construction solutions by Max Berg. Architects all over the world rubbed their eyes in disbelief. Engineers discreetly but steadily tapped on the forehead with their index finger. The concept was an absolute novelty, also because of the material used – reinforced concrete.

The hall is a quatrefoil, i.e. quadruple leaf – symbolically this shape is reflected in our visual identification. The plan of such a complex central building has at least two intersecting axes of symmetry, and the central space is dominated by the height above the side rooms, the walls or the system of supports separated inside the building. In one word, the Centennial Hall’s structure consists of two autonomous elements. Basis in the form of curved arches and ribs and a dome resting freely like a bowler on the head of a pre-war elegant gentleman – radially meeting reinforced concrete ribs, leaning against the lower and upper rings. Terrace roofing system made it possible to install rows of windows, enchantingly illuminating the interior of the Hall. Intentionally raw, uncovered concrete surfaces reflect the sincerity and functionality of the structure, which heralded the beginnings of a modern movement in architecture (modernism).

At the time of its creation, the Hall was a structure with the largest dome span in the world – 65 meters in diameter – overshadowing even the Pantheon in Rome. At that time, only a few steel structures were of a greater size. Height of the structure is impressive 42 metres, while its maximum width is 95 metres. Fast calculation and we already know that we have an area of 14 thousand m². Apart from the central hall in the building, there were designed a lobby to surround the main space. The entire place was to accommodate 10 thousand delighted people.

“Middle school student Hans Brick was fascinated by the Centennial Hall (…). Only today, during his morning lesson, did he find out how many mathematical puzzles there are in this concrete giant. (…)”. This is an excerpt from Marek Krajewski’s novel called Mock, the plot of which is to a large extent connected with the story of creation of the Max Berg’s opus magnum. We refer all inquisitive readers to this absolutely interesting book and to other works of this author – real time travel machines between a contemporary Wrocław and pre-war Breslau.

Chronology of events

Equally impressive as the construction’s momentum was the tempo of its creation. It took only half a year from the acceptance of the design, to the symbolic first shovel and laying the foundations! At the beginning of 1912, there was began the work on the scaffolding and formwork for the four main pillars of the Hall. Preserved archive materials show perfectly how intricate, perforated network was made from wooden beams and steel bars. The next step was to pour in this form a river of liquid concrete. In September 1912, this stage was completed up to the top of the dome and there were started the works of filling it with windows and roof layers.

13 and a half months. This is how long the construction lasted until the acceptance day of the Hall in its raw state (December 1912). A month and a half before the planned date. This innovative construction required equally innovative technical solutions. Around the Hall there were laid the tracks on which operated two electrically powered cranes. They were connected by steel ropes to the top of the tower, standing in the middle of the future Hall, thus creating a cable car with a load capacity of up to 2500 kg above the scaffolding. This was still not enough to lift an adult elephant from the nearby Zoo (an elephant can weigh up to 6000 kg), but enough to set another world record.

Controversy

Reinforced concrete – light and resilient material, despite its excellent technical parameters, was not appreciated by professionals at that time. Certainly not for projects of this scale. The early 20th century still belonged to steel, which had a measurable value in its weight. Despite its enormous weight and significant costs, steel structures dominated the world’s construction sites. Reinforced concrete was questionable, because it had not been tested yet.

That is why the moment when – without a helping hand of scaffolding – the Centennial Hall would have to stand on its own, was dreaded. There were no compromises in the selection of materials. Special cement for the production of concrete, supplied by the Silesia cement plant in Opole, had previously undergone restrictive construction tests. After the steel brittleness tests were performed, it was decided to use rolled steel with increased strength. In places exposed to particular loads, granite from Strzegom – aggregate with the best parameters – was used. Ironwood imported from Australia was used for window woodwork.

Nevertheless, the engineers in charge of the construction and workers were astonished to see Max Berg, who – offering a Deutsche Goldmark – asked a random passer-by to help him to loosen the screw of the first formwork. This way, the Hall entered into its solid, concrete shoes. This moment can be considered a symbolic beginning of a new era in construction.

Jewel in the crown

In order to ensure that the bulky building of the Centennial Hall does not look like a solitary big mound-building termites in the flat landscape of the exhibition grounds, further buildings and recreational spaces had been planned in its vicinity. This had been also required by the momentum this impressive Historical Exhibition was organised, having to include military, economic and cultural achievements of Prussia and – what possibly more importantly – Silesia.

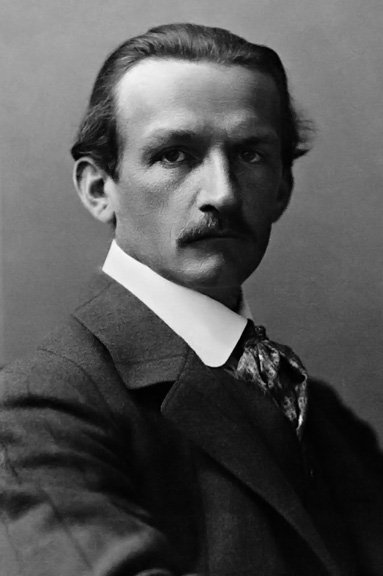

Its superintendent and the director of the Museum of Artistic and Ancient Crafts, Karl Masner, suggested creating a facility which would incorporate the “Frederician” architecture of the previous century. And here, on the stage appears Hans Poelzig – “der Architekt” – another outstanding figure of the design thought in Breslau. His Four Domes Pavilion is a regular quadrilateral building with an extensive courtyard filled with greenery in its symmetrical centre. Just like the Centennial Hall, it was erected from reinforced concrete, and the places where it was necessary to use bricks, Poelzig ordered to be covered with plaster successfully imitating raw concrete (curiosity – construction of the Pavilion cost 200 thousand Deutsche marks at that time, ten times less than the construction of the Centennial Hall). In the architect’s notes we read: “Use of concrete to erect the load-bearing parts of this building made it possible to use antique forms in a new edition, which corresponded to the new building material and also affected the interior design.”

The four domes, from which the facility took its name, crowned each of the wings – in the west and east on a circle plan, in the north and south on an ellipse plan. Visitors to the Exhibition admired the expositions dedicated to Prussian rulers, commanders and private soldiers killed in the wars of the last century. The largest hall housed an impressive 1813 panorama of Breslau by Max Wislicenus, and the aforementioned green courtyard – a fountain with a sculpture of Athena designed by Professor Robert Bednorz. Today, the Four Domes Pavilion is managed by the National Museum in Wrocław, which exhibits works of contemporary art – a lot younger than Athena, but equally beautiful.

Forms. Shapes. Figures. The entire complex is highly geometrical. For example, a half-ellipse. Poelzig bent in this characteristic arch the Pergola surrounding the artificial pond (also half-elliptic) on the north-eastern side of the Centennial Hall. Two rows of poles made of rough, raw concrete are crowned with a grating, on which a vine will gracefully lay down, giving salutary shade in summer. We counted – there are 750 poles and the length of the whole structure is as much as 640 meters.

And finally – the Japanese Garden. Topping on the cake of the exhibition grounds. Founded on the initiative of the count Fritz von Hochberg, a diplomat and orientalist, with the participation of the Japanese gardener Mankichi Arai. It combines the features of several types of gardens: public, water, tea ceremony and pebble beach. In terms of its composition, it is thought-out and consistent like a samurai path. From the main gate of Sukiya-mon over the bridge with the Yumedono Bashi observation pavilion we reach the crossroads. This is the moment of choice. Along the shore of the pond there is a route from the gentle female cascade of Onna-daki to the rapid male cascade of Otoko-daki. On the second trail, crossing the arched bridge Taiko Bashi, we reach the Azumaya tea pavilion.

All the above mentioned items – although already unique as well as of undeniable aesthetic and architectural values – are subordinated to the function or form of the most important item – the Centennial Hall – the pearl in the crown of the Breslau Anno Domini 1913 exhibition grounds.

Melody of the modern times

On multiple occasions before, we mentioned that the Centennial Hall is a futuristic composition, much ahead of its time. What a wonderful and overturn concept it was that in the inside of the Hall there were echoing not avant-garde instruments based on Lee De Forest’s vacuum tubes, but the sounds of pipe organs worthy of the most eminent Bach’s Baroque compositions. We also got used to the prefix “most” when beginning nearly all of the sentences we describe the Hall with. It will therefore come as no surprise that the organ, designed and produced by the Sauer company (still existing) in Frankfurt with 222 registers and 16706 pipes was the largest in the world at the time. During the Second World War the instrument was unfortunately partly destroyed and stolen. The surviving elements can still be heard in the interiors of the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Ostrów Tumski in Wrocław and in the Jasna Góra Monastery.

Architect to the maximum

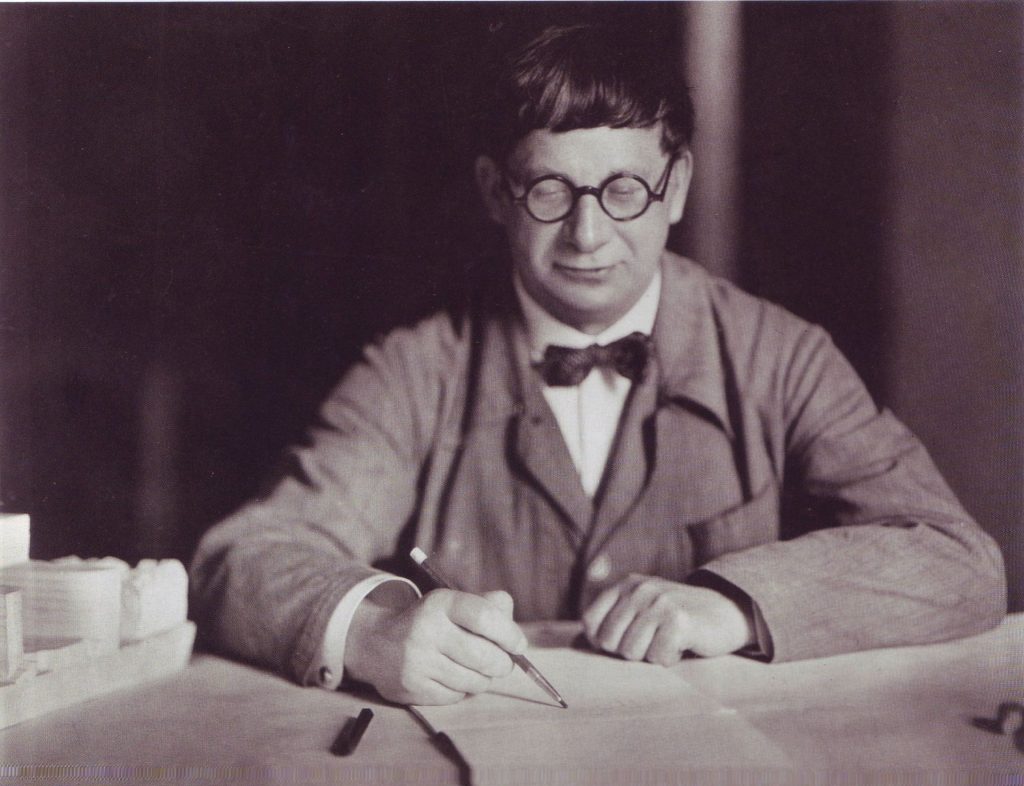

Name of the designer of the Centennial Hall has already been mentioned here so many times that we are probably close to another “most” prefix. So who was Max Berg, the architect? He was born on 17 April 1870 in Szczecin, a pre-war Stettin, died on 22 January 1947 in Baden-Baden. He graduated from the Technical University of Charlottenburg and on 17 December 1908 was elected by the city council of Breslau as the municipal architect official. He lived in a villa on today’s 19 Kopernika Street, which he rebuilt in an English style. The building has been preserved in a good condition – those who love architectural walks are encouraged to venture into the intimate streets of the Dąbie estate.

He was fascinated by Gothic, inspired by expressionism, but his most famous projects are classic examples of modernism. As an urban planner, he proposed dividing the city into zones according to their functions. He was impressed by American metropolises shooting into the sky, but he doubted the validity of copying this model on the European ground. In example of Breslau, he considered the construction of skyscrapers in the key points of the city, located as planned in its space, to be a reasonable compromise. In Wrocław, some buildings of his project survived the historical turmoil, e.g.: the North and South Water Power Plants in the vicinity of the Pomeranian Bridge, the Chapel in the Osobowice Cemetery, the municipal bath in 1 Maria Skłodowska-Curie Street (the student community may associate this building as the location of the Przekręt club) and the former Municipal Children’s Hospital in Hoene-Wroński Street.

The flagship work of Berg is, of course, the Centennial Hall. With this project he proved that – to paraphrase the titles of Wajda’s film dramas – he is “a man of concrete”. And please remember that when we say it, it is like the highest compliment.